|

|

|

|

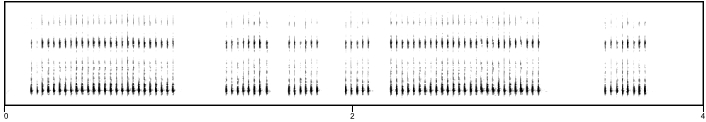

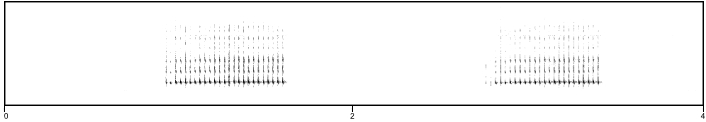

| map | juvenile male | juvenile male | adult male |

|

|

|

|

| adult male | juvenile female | juvenile female | adult female |

|

|

|

|

| adult female | male | female | female |

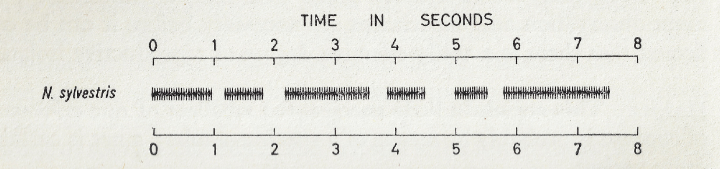

The above song was recorded during courtship and mating of N. sylvestris in southern England. Ragge’s (1965, pp. 136-138) description of this behavior is fascinating. He ends it with these two paragraphs:

The significance of the alternate production of small and large spermatophores is far from clear. It is doubtless unnecessary for a female to receive both spermatophores before fertilization can take place, for in nature males and females are constantly intermingling and one male is not likely to mate with the same female twice in succession. The time spent by the female licking the male's fore wing may have at one time served to allow the sperms to enter her body before the spermatophore was dislodged and eaten; however, she does not now seem inclined to remove the spermatophore, even in the absence of licking behaviour, until at least half an hour has elapsed since she received it. If the male is frustrated in an attempt at mating, he eats the spermatophore and produces a small one again at the next attempt.

It should be mentioned that the male may begin his courtship behaviour and even produce a spermatophore in the absence of a female, and will in fact discourage her from mounting him until a short time after its production.

This is the only alien species that was first discovered at localities so distant from one another that it seems uncertain whether the two established populations are the result of a single trans-Atlantic shipment or from two such shipments, possibly from source populations as distinct as southern England, continental Europe, and northern Africa. These source populations have been established for lengthy periods (at least for thousands of years) and therefore should have developed genetic differences that can be easily detected. However, an initial inspection of systematic literature has revealed no such studies have occurred. In fact, the only populations that have been carefully studied are in southern England, where all known populations seem to be "south of the Thames River." Some of these populations have been carefully studied by David Ragge (1965). These studies revealed a two-year life history with some very interesting features. The following seven paragraphs are a verbatim quote from pp. 133-135 of David R. Ragge’s Grasshoppers, crickets and cockroaches of the British Isles.

Life History The life history of this species is most interesting in that its complete cycle occupies two years, unlike that of any of our other Saltatoria except the Mole-cricket. The eggs pass the winter in a resting phase and generally begin to hatch during June. The young nymphs pass through their earlier instars during the course of the summer, usually reaching the fifth (occasionally the sixth) instar by autumn. At this stage the nymphs measure about 5 mm. in length, and in the females minute traces of the developing ovipositor may be seen with the aid of a microscope. The half-grown Wood-crickets then spend the winter in a resting phase: growth ceases and there are no further moults for some months. They do not undergo true hibernation, however, and may be found in a more or less active state during mild spells at any time of the winter.

The nymphs resume a fully active life in April of the following year. The fifth moult soon takes place, and the last three follow during May and June. The sixth-instar nymphs are very similar to those of the preceding instar, though the rudiments of the ovipositor become slightly larger in the females. In the seventh instar the ovipositor measures about 1 mm. and is visible to the naked eye; in the eighth and last nymphal instar it reaches a length of about 3 mm. The wing-rudiments first appear in the seventh instar in both sexes and are clearly visible in the eighth.

If the spring weather is favourable the first adults may appear in June, though most nymphs undergo the final moult during July and a few last-instar nymphs are to be found in August. Maturity is reached about 1-2 weeks after the final moult and the breeding season lasts from July until November.

The eggs are laid singly just below the surface of the ground. The abdomen is raised until the ovipositor can probe the soil vertically, and when a suitable spot has been found this instrument is inserted up to the hilt. A single egg is laid and the ovipositor is then withdrawn gradually in such a way as to fill the hole with soil. Egg-laying continues until the autumn, and the total number of eggs laid by a single female (assuming that she remains alive and healthy throughout the breeding season) is about 200.

Most of the adults die off towards the end of the year, but a few manage to survive the winter and are still to be found in the following spring. These aged Wood-crickets have achieved a life-span of almost two years since hatching and nearly three years since the eggs were laid. Few other Saltatoria can rival this, though in this country the Mole-cricket, which in our latitudes has a life-span after hatching of more than two years, holds the record.

As a result of this two-year life-cycle the Wood-cricket may be found in at least two, and usually three, different stages of development throughout the year. During the winter its eggs lie dormant below the surface of the ground while the half-grown nymphs indulge in occasional bursts of activity above them, and a few senile adults are scattered here and there. When the eggs begin to hatch in June the nymphs that have overwintered will be in their seventh or eighth instar. At this time only these two stages of development will normally be represented, as even the hardiest of adults will usually have died off. In late summer all the individuals that passed the winter in the nymphal stage will have become adult, and the newly hatched nymphs will be passing through their early instars; there will also be freshly laid eggs in the ground.

It is also a most interesting outcome of this biennial life history that the British Wood-cricket must be divided into two distinct strains, which are rarely if ever able to interbreed. This is because the adults of one year rarely overlap during their own adult life with adults of either the preceding or following years, so that when one strain is adult the other is still in the nymphal stage and vice versa. Although it is true that a few adults survive the winter, most of these die early in the year and it is doubful if those that still remain have sufficient life left in them for courtship and mating. To the extent that these two strains are unable to breed with each other, one can speak of the 'Even-year Wood-cricket' and 'Odd-year Wood-cricket', but more observation and experiment are necessary before it can be confirmed that there is a really effective degree of reproductive isolation.

| References: | Ragge 1965, pp132-138. |

| Nomenclature: | OSF (Orthoptera Species File Online). |

|

|